The gods of Asatru: Tyr (Tiw, Zio, Tiwaz)

This god plays a relatively small role in the mythology as it survives in the Eddas; nevertheless, every description of him which survives points to a much larger significance in early Germanic religion overall. His name in Old Norse, “Týr,” is one of the generic words for “god”; it is cognate to the Latin “deus” and the Greek “Zeus.” It is generally thought that Tiw was the Germanic version of the Indo-European Sky-Father god, whose position as chief of the gods was then gradually usurped by Wodan. In understanding Tiw, however, it is necessary to consider his specific evolution among the Germanic peoples; neither the Romans who came into contact with his cult at the beginning of the Common Era nor the Germanic folk of later eras who tried to equate their own or their ancestors' gods with the gods of the Greeks and Romans considered him to be similar to Jupiter/Zeus. Rather; he was Mars Thingsus, “Mars of the Thing (Judgement-Assembly)”;(26) among the names of the days of the week, which were adapted by the Ger-manic folk before Christianization, Tiw's Day – modern Tuesday – was not the day of Jupiter, but dies Martis, the day of Mars. Tacitus reports that the Germans held “Mercury and Mars” highest of all the gods, and no successful argument for seeing this pair as anyone other than Wodan and Tiw has yet been advanced.

Although Tiw's most obvious character is that of a warlike god, he is also a god of contracts and of law, as the title Mars Thingsus would imply. The Old Icelandic Rune Poem calls him “the ruler of the temple” even as it glosses his name as “Mars.” Dumézil presents Tiw as the Judge-King equivalent to the Vedic Mitra, the sovereign who rules by law, the meotod (“measurer”) – an originally heathen title which remained current in Anglo-Saxon and was eventually co-opted by Christianity for their god. According to his model, the Judge-King ruled together with the furious and unpredictable Magician-King. “The cruel, magical Ódhinn is thus contrasted with Týr, as Varuna, god of night, is contrasted with Mitra, god of day.”(27) In the Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem, the names of the gods – except for Ing, who was euhemerized to “the hero” – were deleted and replaced with hononyms which were also appropriate in context. Just as the “Os” (Ase) Wodan became “oss,” “(Mouth), the chieftain of all speech,” so did Tiw become “tir,” the star, which “holds troth well / with athelings ever fares on course, / over mists of night and never weakens.”

This god plays a relatively small role in the mythology as it survives in the Eddas; nevertheless, every description of him which survives points to a much larger significance in early Germanic religion overall. His name in Old Norse, “Týr,” is one of the generic words for “god”; it is cognate to the Latin “deus” and the Greek “Zeus.” It is generally thought that Tiw was the Germanic version of the Indo-European Sky-Father god, whose position as chief of the gods was then gradually usurped by Wodan. In understanding Tiw, however, it is necessary to consider his specific evolution among the Germanic peoples; neither the Romans who came into contact with his cult at the beginning of the Common Era nor the Germanic folk of later eras who tried to equate their own or their ancestors' gods with the gods of the Greeks and Romans considered him to be similar to Jupiter/Zeus. Rather; he was Mars Thingsus, “Mars of the Thing (Judgement-Assembly)”;(26) among the names of the days of the week, which were adapted by the Ger-manic folk before Christianization, Tiw's Day – modern Tuesday – was not the day of Jupiter, but dies Martis, the day of Mars. Tacitus reports that the Germans held “Mercury and Mars” highest of all the gods, and no successful argument for seeing this pair as anyone other than Wodan and Tiw has yet been advanced.

Although Tiw's most obvious character is that of a warlike god, he is also a god of contracts and of law, as the title Mars Thingsus would imply. The Old Icelandic Rune Poem calls him “the ruler of the temple” even as it glosses his name as “Mars.” Dumézil presents Tiw as the Judge-King equivalent to the Vedic Mitra, the sovereign who rules by law, the meotod (“measurer”) – an originally heathen title which remained current in Anglo-Saxon and was eventually co-opted by Christianity for their god. According to his model, the Judge-King ruled together with the furious and unpredictable Magician-King. “The cruel, magical Ódhinn is thus contrasted with Týr, as Varuna, god of night, is contrasted with Mitra, god of day.”(27) In the Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem, the names of the gods – except for Ing, who was euhemerized to “the hero” – were deleted and replaced with hononyms which were also appropriate in context. Just as the “Os” (Ase) Wodan became “oss,” “(Mouth), the chieftain of all speech,” so did Tiw become “tir,” the star, which “holds troth well / with athelings ever fares on course, / over mists of night and never weakens.”

It is likely that Tiw (Tyr) was the original “irmin- god,” the greatest of the gods, to whom the Saxon Irminsul (Irmin-Pillar) was dedicated. On the daily human level, the Irminsul is embodied by the house-pillars; on the cosmic level it is the World-Tree, which preserves the levels of being by holding them apart and at the same time, as the central axis of the universe, connects them; and this is shown in the shape of the rune tiwaz, which can be interpreted either as the spear or as the pillar holding up the heavens. In the Old High German “Hildebrantslied,” the warrior Hildebrant calls upon “irmingot” (“the Irmin-god”) and “waltant got” (“the ruling god”) to witness the terrible fate which “Woe-Wyrd” has wrought for him. These titles, used as they are to invoke the laws of society and nature against the caprice of Wyrd which has brought him to a fatal conflict with his own son, are far more likely to be addressed to Tiw than to Wodan, who was blamed for setting strife between kinsmen, not called upon in the attempt to turn it away.

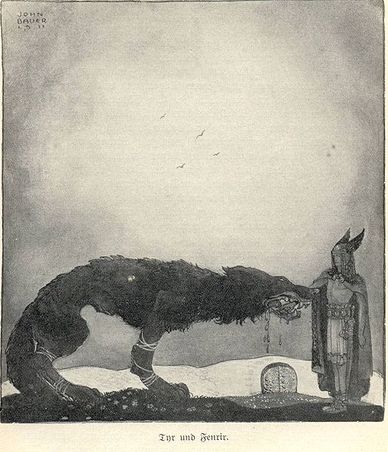

The one significant myth which has survived about Tiw (Tyr) is the story of the binding of the Wolf Fenrir, the son of Loki and Angrboda, as told in the Prose Edda. This wolf grew so large that none except Týr dared to feed him. At last the gods began to be afraid and decided to bind him. Fenrir agreed to allow it if one of the gods would lay his hand in his mouth as a pledge of troth. “And each of the Ases looked at the other, and none of them was willing to lose his hand, until Týr reached forward his right hand and lay it in the mouth of the Wolf.” Then Fenrir was bound, and the harder he struggled the more firmly the band lay upon him, and “all laughed except Týr; he lost his hand.” From this, the wrist is called the “wolf's joint.”

The rune tiwaz is named after Tiw; its stave-shape shows the spear which may have been his particular weapon before it was Wodan's. The Old Norwegian Rune-Poem says of this stave that “(Týr) is the one-handed among the Ases”; the Old Icelandic Rune-Poem says, “(Týr) is the one-handed Ase / and the wolf's leavings, / and the temple's ruler.” This last probably refers to his strong role in the religious life of the folk.

The one significant myth which has survived about Tiw (Tyr) is the story of the binding of the Wolf Fenrir, the son of Loki and Angrboda, as told in the Prose Edda. This wolf grew so large that none except Týr dared to feed him. At last the gods began to be afraid and decided to bind him. Fenrir agreed to allow it if one of the gods would lay his hand in his mouth as a pledge of troth. “And each of the Ases looked at the other, and none of them was willing to lose his hand, until Týr reached forward his right hand and lay it in the mouth of the Wolf.” Then Fenrir was bound, and the harder he struggled the more firmly the band lay upon him, and “all laughed except Týr; he lost his hand.” From this, the wrist is called the “wolf's joint.”

The rune tiwaz is named after Tiw; its stave-shape shows the spear which may have been his particular weapon before it was Wodan's. The Old Norwegian Rune-Poem says of this stave that “(Týr) is the one-handed among the Ases”; the Old Icelandic Rune-Poem says, “(Týr) is the one-handed Ase / and the wolf's leavings, / and the temple's ruler.” This last probably refers to his strong role in the religious life of the folk.

(Excerpt from the Asatru/Heathen book Teutonic Religion by Kveldulf Gundarsson. Used with permission. To purchase an e-copy of the entire book Teutonic Religion click on the link.