SOUL AND THE AFTERLIFE

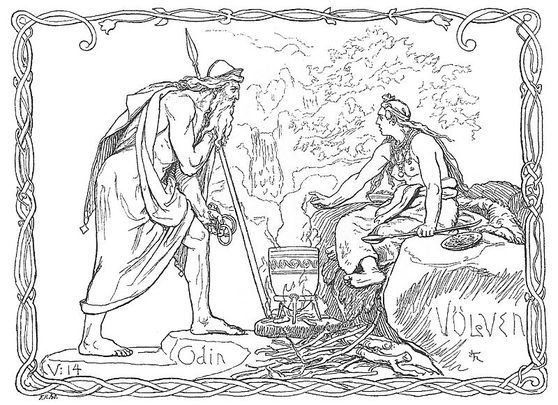

IT IS TOLD IN “VÖLUSPA” how, after the creation of the world, Wodan and his brothers Hoenir and Lódurr “found on land little in main, / Ash and Elm, without ørlög” – that is to say, still outside the realm of causality. Lacking any power to influence the shape of wyrd, Ash and Elm are still untouched by it; they have no ørlög because they have no effective existence. These two trees, the first humans, “possessed not önd had not wod, / nor hair nor shape nor good appearance. / Önd gave Wodan, wod gave Hoenir, / hair gave Lódurr and good appearance.” Önd is an Old Norse word which can be used for the breath of life or for the soul itself; wod signifies all the higher mental faculties which are awakened through its workings; hair, shape, and good appearance are all expressions of the fiery force of life which appears as both spiritual and physical strength. Hoenir and Lódurr are, in fact, aspects of Wodan himself, which explains how it is that Hoenir gives to humans the gift of wod. As firstly a god of the air, Wodan is responsible for the airy soul which appears in the earthly world as the breath of life; wod appears as a draught of intoxicating liquid, therefore it is given by the watery Hoenir; the might which Lódurr gives is all characterized by the fire of energy itself.

When Ash and Elm have been given these three gifts, they are no longer “without ørlög”; they have become, and therefore are both bound by Wyrd and capable of shaping her turnings. To have “soul” is to bear doom and power together; the two are shaped at one time by the weight of what is, which determines what shall be. From the moment they breathe in the önd of life, they are doomed to die; their ørlög is the fourth major component of their “souls.” This is the aspect of soul which is given to a child in the naming-ceremony, without which it is not considered human.

In Germanic tradition, these four primal elements of the psychic being were divided into a number of different aspects, which often overlap in some areas but which are nevertheless distinct and important to understand as separate entities. In Teutonic Magic, I discussed the aspects of the soul which are most important in magical workings: hugr (reason) and minni (memory); hamingja (“luck”, mana); fylgja (fetch); hamr (“hide” or spiritual form). In addition to these, the soul also bears mood, might and main, ørlög, and life-age (aldr).

First among these is the hugr, which is specifically taken to mean the conscious mind; the verb derived from it, hyggja, is generally used for “to think” or “to intend.” When contrasted with the minni, as in the case of Wodan's ravens Huginn and Muninn, it denotes the intellectual/left-brain process; when used by itself, it seems to encompass both conscious thought and intuition/emotion together. To know something with the hugr is to know it, not only intellectually, but with all the awareness of the soul; the hugr is often what tells you whether to trust someone or not or what the results of an action are likely to be. The hugr is your courage and the strength of your mind as well as your wisdom. It also denotes the quality of thought and feeling; you can say that your hugr is well-disposed or ill-disposed towards someone. The hugr of another can be seen in the shape of an animal similar to the fetch; its nature shows the person's character and its actions show his/her intentions towards one.

Closely related to hugr is módhr. Both are used to describe the quality of feeling or thought; however, módhr (the word from which our modern “mood” comes), does not carry the sense of consciousness or thought which is generally shown by hugr; módhr is generally used to mean “courage,” “heart,” or “nature.” “When Thor is altogether himself, he appears in his godly módhr (ásmódhr); the giants put on fiendish módhr when they assume their full nature... To assume giant's módhr or bring it into play is understood to imply all such peculiarities – violence and ferocity as well as features – that show him a being of demon land.”(1) To describe his heroism, Beowulf is described as modig, which might be translated as “mood-full,” If your mood is strong, then you are mighty and brave; if it is weak or low, then activity and strength are lacking.

The three main forms of vital power are called hamingja, might, and main. Hamingja is often translated as “luck”; it appears as the aura of power around every person. The hamingja is what vitalizes the other aspects of the soul such as the fetch and the walkyrige. Unlike the mood, it can be transmitted to other people, sent forth from the body, or even stored in an external item like an electrical charge. It corresponds most closely to the Polynesian concept of “mana,” or undifferentiated magical force which can be used for anything, but which certain persons and items have in greater quantity than others. Might and main are unlike hamingja in that they represent a combination of earthly strength and soul-force, and they cannot be transferred to another person or thing.

Though our ancestors quite often thought of physical and spiritual strength as being one and the same, this was not always so. One of the greatest heroes of the Danes, the king Hrólfr kraki, was given his nickname “kraki” or “stick” in reference to his small build. Hrólfr was not physically overwhelming, but his great wisdom, mood, and hamingja more than made up for his size, although he might have lacked in earthly might and main when compared to some of the warriors such as the bear-hero Bödhvar-Bjarki who fought in his band.

Closely related to ørlög is the aldr, “life-age,” which carries the sense both of vital power and of “fate,” as well as of honor. In the Prose Edda, it is said of both the three Norns Wyrd, Werthende, and Should, and of the individual norns who come to every child that they “shape aldr,” and that this shaping determines both the length and the quality of life. The life-age cannot be identical to ørlög, because it can be lost or taken; it may, rather, be thought of as a store of might which is kept within from birth, the nature of which determines its keeper's actions and their consequences. Dishonorable deeds lessen it; honorable deeds make it wax and strengthen. It may be seen as the vital essence of the self, which determines strength of soul by its quantity and character by its quality

The fetch (Old Norse fylgja) is a semi-independent aspect of the soul, whose shape reflects its owner's true character. Especially strong and noble people often have bear-fetches; the very fierce have wolves; the cunning have foxes, and so forth. The fetch can be seen at any time by folk with soul-sight, but it only appears to those without psychic vision shortly before death. To see your fetch bloody or ill is a sure sign of approaching death; its condition reflects that of its owner. The fetch can be sent out from the body to bring back knowledge, or it is possible to consciously inhabit your fetch's shape when faring away from your body.

Germanic concepts of the afterlife varied between different areas, time periods, and dedication to various gods. Their only really consistent element was the emphasis on the family as a continuous unit spanning the worlds of the dead and the living. One of the most common descriptions of death was that of going to join one's “kinsmen who have gone before”; whether spiritually in the halls of the gods or physically within the burial mound.

The aspect of the Germanic afterlife which is best known in modern popular culture is the belief in Walhall (Valhöll, or Valhalla), the “Hall of the Slain.” As the name and many of the literary references imply, Walhall was usually, though not invariably, seen as the goal of those slain in battle. Wodan sends the walkyriges (valkyrjur) to choose which heroes should fall in a fight and to bring their souls back to Walhall. These warriors – the einherjar or “single champions” – fight every day, coming back to life to feast every night. At the end of all things, they will fight against the giants to make the rebirth of the cosmos possible. It should be noted, however, that Wodan's halls, Walhall and Válaskjalf (“Hall of Slain Warriors”), were not limited to those who fell in fight. Egill Skallagrímsson says of his son Bödvar who was drowned that “Ódhinn took him to himself…..My son is come to Ódhinn's house, the son of my wife to visit his kin .….I remember still that Ódhinn raised up into the home of the gods the ash-tree of my race, that which grew from me, the kin-branch of my wife.” The belief in Walhall may have been connected with the practice of cremation. Initiation of this practice is attributed to Wodan in Ynglinga saga: “He bade that they burn all the dead and bear their possessions on to the firebale with them. He said that every man should come to Valhöll with such riches as he had with him on the firebale and that each should use what he had himself buried down in the earth. They should bear the ashes out on the sea or bury them down in the earth ...” The cremation of important persons followed by the burial of the ashes and raising a mound is verified by the great mounds at Old Uppsala; the two that have been excavated both contained cremated bodies together with partially melted weapons and gold ornaments.

Despite the popular conception, not all warriors slain in battle go to Walhall. It is written in “Grímnismál” that “Folkvangr is the ninth (hall) where Freyja rules and chooses who sits in her hall. / Half of the slain she chooses each day the other half Ódhinn has.” This stanza may hark back to very ancient beliefs about burial practices and the fate of the soul. Those buried in the earth naturally belonged to the Wanic powers and particularly to the Frowe; given that cremation seems to have been largely associated with the cult of Wodan, the “Grímnismál” passage may be a statement of the spiritual consequences of the fact that the battle-slain dead were burned and buried in roughly even numbers (though this varied widely with place and period).

The popular conception of the Norse afterlife, again, holds that whoever did not die fighting went to the realm of Hel, the grim world below the earth. This conception is largely a product of the Prose Edda, in which Snorri puts forth this view, describing Hel's domain in relatively horrific terms.

The name of the goddess Hel had already undergone semantic contamination among the Christianized continental Germanic peoples and the Anglo-Saxons, having been superimposed upon the terrible underworld of Indo-Iranian tradition as part of the conversion process. After the identification of Hella's realm with the southern conception of a world of torment, the North was then exposed to the familiar name Hell as part of Christianity, and assimilated the unfamiliar concept of the underworld as a realm of punishment without much difficulty. Thus the Christian concept of Hel's realm almost certainly distorted Snorri's presentation to some degree. In point of fact the goddess Hella appears in a form which makes her consistent with the nature of the other Wanic powers: she is half-dead and ugly, half-living and beautiful. This description in Snorri seems to preserve a deep understanding of the relationship between the mysteries of death and fertility. On the one hand, Hel is the earth as the terrifying grave; on the other, she is the earth as the mother who protects and nurtures the buried soul-seed, which she may bring to life again. This is precisely the function she carries out on a cosmic scale at Ragnarök; while everything else is destroyed, she preserves the souls of Baldr and his slayer Hödhr, bringing them forth to live again when the battle is done and the worlds recreated.

IT IS TOLD IN “VÖLUSPA” how, after the creation of the world, Wodan and his brothers Hoenir and Lódurr “found on land little in main, / Ash and Elm, without ørlög” – that is to say, still outside the realm of causality. Lacking any power to influence the shape of wyrd, Ash and Elm are still untouched by it; they have no ørlög because they have no effective existence. These two trees, the first humans, “possessed not önd had not wod, / nor hair nor shape nor good appearance. / Önd gave Wodan, wod gave Hoenir, / hair gave Lódurr and good appearance.” Önd is an Old Norse word which can be used for the breath of life or for the soul itself; wod signifies all the higher mental faculties which are awakened through its workings; hair, shape, and good appearance are all expressions of the fiery force of life which appears as both spiritual and physical strength. Hoenir and Lódurr are, in fact, aspects of Wodan himself, which explains how it is that Hoenir gives to humans the gift of wod. As firstly a god of the air, Wodan is responsible for the airy soul which appears in the earthly world as the breath of life; wod appears as a draught of intoxicating liquid, therefore it is given by the watery Hoenir; the might which Lódurr gives is all characterized by the fire of energy itself.

When Ash and Elm have been given these three gifts, they are no longer “without ørlög”; they have become, and therefore are both bound by Wyrd and capable of shaping her turnings. To have “soul” is to bear doom and power together; the two are shaped at one time by the weight of what is, which determines what shall be. From the moment they breathe in the önd of life, they are doomed to die; their ørlög is the fourth major component of their “souls.” This is the aspect of soul which is given to a child in the naming-ceremony, without which it is not considered human.

In Germanic tradition, these four primal elements of the psychic being were divided into a number of different aspects, which often overlap in some areas but which are nevertheless distinct and important to understand as separate entities. In Teutonic Magic, I discussed the aspects of the soul which are most important in magical workings: hugr (reason) and minni (memory); hamingja (“luck”, mana); fylgja (fetch); hamr (“hide” or spiritual form). In addition to these, the soul also bears mood, might and main, ørlög, and life-age (aldr).

First among these is the hugr, which is specifically taken to mean the conscious mind; the verb derived from it, hyggja, is generally used for “to think” or “to intend.” When contrasted with the minni, as in the case of Wodan's ravens Huginn and Muninn, it denotes the intellectual/left-brain process; when used by itself, it seems to encompass both conscious thought and intuition/emotion together. To know something with the hugr is to know it, not only intellectually, but with all the awareness of the soul; the hugr is often what tells you whether to trust someone or not or what the results of an action are likely to be. The hugr is your courage and the strength of your mind as well as your wisdom. It also denotes the quality of thought and feeling; you can say that your hugr is well-disposed or ill-disposed towards someone. The hugr of another can be seen in the shape of an animal similar to the fetch; its nature shows the person's character and its actions show his/her intentions towards one.

Closely related to hugr is módhr. Both are used to describe the quality of feeling or thought; however, módhr (the word from which our modern “mood” comes), does not carry the sense of consciousness or thought which is generally shown by hugr; módhr is generally used to mean “courage,” “heart,” or “nature.” “When Thor is altogether himself, he appears in his godly módhr (ásmódhr); the giants put on fiendish módhr when they assume their full nature... To assume giant's módhr or bring it into play is understood to imply all such peculiarities – violence and ferocity as well as features – that show him a being of demon land.”(1) To describe his heroism, Beowulf is described as modig, which might be translated as “mood-full,” If your mood is strong, then you are mighty and brave; if it is weak or low, then activity and strength are lacking.

The three main forms of vital power are called hamingja, might, and main. Hamingja is often translated as “luck”; it appears as the aura of power around every person. The hamingja is what vitalizes the other aspects of the soul such as the fetch and the walkyrige. Unlike the mood, it can be transmitted to other people, sent forth from the body, or even stored in an external item like an electrical charge. It corresponds most closely to the Polynesian concept of “mana,” or undifferentiated magical force which can be used for anything, but which certain persons and items have in greater quantity than others. Might and main are unlike hamingja in that they represent a combination of earthly strength and soul-force, and they cannot be transferred to another person or thing.

Though our ancestors quite often thought of physical and spiritual strength as being one and the same, this was not always so. One of the greatest heroes of the Danes, the king Hrólfr kraki, was given his nickname “kraki” or “stick” in reference to his small build. Hrólfr was not physically overwhelming, but his great wisdom, mood, and hamingja more than made up for his size, although he might have lacked in earthly might and main when compared to some of the warriors such as the bear-hero Bödhvar-Bjarki who fought in his band.

Closely related to ørlög is the aldr, “life-age,” which carries the sense both of vital power and of “fate,” as well as of honor. In the Prose Edda, it is said of both the three Norns Wyrd, Werthende, and Should, and of the individual norns who come to every child that they “shape aldr,” and that this shaping determines both the length and the quality of life. The life-age cannot be identical to ørlög, because it can be lost or taken; it may, rather, be thought of as a store of might which is kept within from birth, the nature of which determines its keeper's actions and their consequences. Dishonorable deeds lessen it; honorable deeds make it wax and strengthen. It may be seen as the vital essence of the self, which determines strength of soul by its quantity and character by its quality

The fetch (Old Norse fylgja) is a semi-independent aspect of the soul, whose shape reflects its owner's true character. Especially strong and noble people often have bear-fetches; the very fierce have wolves; the cunning have foxes, and so forth. The fetch can be seen at any time by folk with soul-sight, but it only appears to those without psychic vision shortly before death. To see your fetch bloody or ill is a sure sign of approaching death; its condition reflects that of its owner. The fetch can be sent out from the body to bring back knowledge, or it is possible to consciously inhabit your fetch's shape when faring away from your body.

Germanic concepts of the afterlife varied between different areas, time periods, and dedication to various gods. Their only really consistent element was the emphasis on the family as a continuous unit spanning the worlds of the dead and the living. One of the most common descriptions of death was that of going to join one's “kinsmen who have gone before”; whether spiritually in the halls of the gods or physically within the burial mound.

The aspect of the Germanic afterlife which is best known in modern popular culture is the belief in Walhall (Valhöll, or Valhalla), the “Hall of the Slain.” As the name and many of the literary references imply, Walhall was usually, though not invariably, seen as the goal of those slain in battle. Wodan sends the walkyriges (valkyrjur) to choose which heroes should fall in a fight and to bring their souls back to Walhall. These warriors – the einherjar or “single champions” – fight every day, coming back to life to feast every night. At the end of all things, they will fight against the giants to make the rebirth of the cosmos possible. It should be noted, however, that Wodan's halls, Walhall and Válaskjalf (“Hall of Slain Warriors”), were not limited to those who fell in fight. Egill Skallagrímsson says of his son Bödvar who was drowned that “Ódhinn took him to himself…..My son is come to Ódhinn's house, the son of my wife to visit his kin .….I remember still that Ódhinn raised up into the home of the gods the ash-tree of my race, that which grew from me, the kin-branch of my wife.” The belief in Walhall may have been connected with the practice of cremation. Initiation of this practice is attributed to Wodan in Ynglinga saga: “He bade that they burn all the dead and bear their possessions on to the firebale with them. He said that every man should come to Valhöll with such riches as he had with him on the firebale and that each should use what he had himself buried down in the earth. They should bear the ashes out on the sea or bury them down in the earth ...” The cremation of important persons followed by the burial of the ashes and raising a mound is verified by the great mounds at Old Uppsala; the two that have been excavated both contained cremated bodies together with partially melted weapons and gold ornaments.

Despite the popular conception, not all warriors slain in battle go to Walhall. It is written in “Grímnismál” that “Folkvangr is the ninth (hall) where Freyja rules and chooses who sits in her hall. / Half of the slain she chooses each day the other half Ódhinn has.” This stanza may hark back to very ancient beliefs about burial practices and the fate of the soul. Those buried in the earth naturally belonged to the Wanic powers and particularly to the Frowe; given that cremation seems to have been largely associated with the cult of Wodan, the “Grímnismál” passage may be a statement of the spiritual consequences of the fact that the battle-slain dead were burned and buried in roughly even numbers (though this varied widely with place and period).

The popular conception of the Norse afterlife, again, holds that whoever did not die fighting went to the realm of Hel, the grim world below the earth. This conception is largely a product of the Prose Edda, in which Snorri puts forth this view, describing Hel's domain in relatively horrific terms.

The name of the goddess Hel had already undergone semantic contamination among the Christianized continental Germanic peoples and the Anglo-Saxons, having been superimposed upon the terrible underworld of Indo-Iranian tradition as part of the conversion process. After the identification of Hella's realm with the southern conception of a world of torment, the North was then exposed to the familiar name Hell as part of Christianity, and assimilated the unfamiliar concept of the underworld as a realm of punishment without much difficulty. Thus the Christian concept of Hel's realm almost certainly distorted Snorri's presentation to some degree. In point of fact the goddess Hella appears in a form which makes her consistent with the nature of the other Wanic powers: she is half-dead and ugly, half-living and beautiful. This description in Snorri seems to preserve a deep understanding of the relationship between the mysteries of death and fertility. On the one hand, Hel is the earth as the terrifying grave; on the other, she is the earth as the mother who protects and nurtures the buried soul-seed, which she may bring to life again. This is precisely the function she carries out on a cosmic scale at Ragnarök; while everything else is destroyed, she preserves the souls of Baldr and his slayer Hödhr, bringing them forth to live again when the battle is done and the worlds recreated.

(Excerpt from the book Teutonic Religion by Kveldulf Gundarsson .To purchase an entire e-copy of the Asatru/Heathen book Teutonic Religion click on the link.